AFTER WATCHING CNBC’s excerpts of Federal Reserve Board Chairman Alan Greenspan’s latest semiannual appearance on Capitol Hill, George Brockway phoned us. “I have some bad news,” said our veteran economics columnist cheerfully. “Greenspan may be reading THE NEW LEADER.” But his actual purpose was to alert us that he was pursuing the entire videotaped hearing. If he found his eyes and ears had not deceived him, the next installment of “The Dismal Science” would be devoted to it.

Why there was a tinge of uncharacteristic excitement in Brockway’s voice will become apparent when you read “What Greenspan Really Told Congress” (page l3). Our own actual purpose here is to alert you to the publication in October of Economists Can Be Bad for Your Health, his third book since starting his second career in these pages almost 14 years ago.

His first career, in publishing, ran some 46 years. Following graduation in 1936 from Williams College and (jobs being scarce) a year in graduate school at Yale on a fellowship, Brockway went to work for McGraw Hill in 1941 he joined W.W. Norton, where before long his editorial talents and his business acumen put him on the up escalator. By 1958 he was named president, and in 1976 he assumed the chairmanship of the now employee-owned company. Along the way, he fashioned Norton into the major independent publisher it is today.

When rampaging Reagan-era inflation and 21 per cent loan rates threatened to undermine the house he built, bankers became Brockway’s bête noire and people-friendly economics his preoccupation. Already an occasional contributor to the NL on foreign policy matters, he did several pieces for us in 1981 on his new subject. Then he proposed the column that began running in alternate issues the next January, two years prior to his retirement. His relaxed style, quiet wit and devastating debunking of mainstream wisdom soon attracted a wide audience. Even those who were infuriated by his central thesis – that “economics is a branch of ethics, not of natural science” – could not resist reading him. At a recent conference Brockway met Martin Feldstein, who was a member of Ronald Reagan’s Council of Economic Advisers. “I always read you,” confessed Feldstein, “but you’re all wrong.”

Brockway’s first two books, published by Harper, were Economics: What Went Wrong and Why and Some Things to Do About It (1985) and The End of Economic Man (1991). The latter was brought out in paperback by Norton, which is about to issue a third revised edition. As for Economists Can Be Bad for Your Health, also from Norton, we neglected to mention that it is a selection of his NL columns. Previewing it, Jeff Faux, president of the Economic Policy Institute, wrote: “George Brockway is a national treasure. His new book picks apart foolish economic dogma with deft application of common sense in simple English. He entertains us and inspires us to think for ourselves. May he write forever.”

Amen.

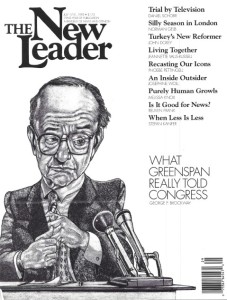

OUR COVER drawing of Alan Greenspan is by Mwaura Kirore.